Training Tales: Valérie Wartelle on textile art with Claudy Jongstra in the Netherlands

9th May 2022

QEST William Parker Scholar Valerie Wartelle is a textile artist specialising in wet felting. QEST funding enabled her to spend time in the Netherlands with Dutch artist and activist Claudy Jongstra, a world-leader in wool crafts. The training at ‘Farm of the World’, Friesland enabled her to deepen and expand her understanding of the materials and processes she engages with. Here she recounts her experience learning about natural pigments from the botanical research garden, preparing of raw wool using natural dye processes in the colour lab and more.

As I drove away from the village of Spannum for the last time, I felt a sense of deep gratitude to have been able to engage with the world and vision of wool activist, Claudy Jongstra. My three-month internship was an immersive experience; a chance to leave my own practice at home and surrender myself to the pursuit of learning and discovery.

I have long been an admirer of Claudy Jongstra’s majestic felt artworks and architectural installations. Their organic surfaces and rich colours invite us to reconnect with the land, bring it into our home or workplace and nurture our wellbeing.

A proponent of Artivism, Jongstra combines conservation with collaboration to preserve craft skills and revive the use of wild plants dyes, underpinned by ecologically-just models and circular production systems. My anticipation at meeting Claudy and experiencing first-hand the workings of a fast-flowing and innovative artist studio could not be understated.

After months of planning, a travel embargo and quarantine on arrival, I joined Claudy Jongstra Studio in early January. The studio barn, dye lab, office, interns’ accommodation and family home are all located in a charming village in rural Friesland. It sure had been a long time since I’d shared a house with strangers, away from the comforting bubble of my home, family, and friends. I did wonder, how would I fair?

A few kilometres away, in the village of Húns is the biodynamic farm overseen by Claudy’s partner, Claudia. The farm with its period greenhouse, botanical research garden, rewilding plots, and indigenous Drenthe Heath sheep provides some of the essential raw materials to support the work of the studio.

The studio is a large multifunctional barn, adjusting its layout and activities in response to the latest project, and expertly managed by the chef d’atelier, Anneleen.

From day one I was introduced to the fundamental skills of hand carding and spinning, central to the making of each artwork. Both felt intensely absorbing yet soothing, as I modulated my rhythm and proprioception in search of that perfect colour blend or yarn count.

I was particularly curious to learn about the dye plants and processes involved in Jongstra’s work. During my time in the lab, I worked with researchers from the University of Amsterdam and the Cultural Heritage of the Netherlands to recreate Eise Eisinga’s Celestial Blue recipes from 1808. The recipes describe the art of blue vat dyeing with the indigenous woad plant (Pastel) – a practice which had faded into oblivion, but is currently undergoing a revival in Europe.

I conducted three dye experiments starting with greenwoad balls fermentation, followed by the addition of woad pigment and finally indigo pigment. Over the course of 10 days, I nurtured and fed the vat, logging my observations. Of note was the near-intolerable stench that grew increasingly pungent as the greenwoad paste broke down. It eventually paid off, and I was delighted to produce some of my own celestial blues and pure woad blues. The experiment provided valuable information towards the research, and a paper is due to be presented at the Dyes in History and Archeology conference in Sweden, in October later this year.

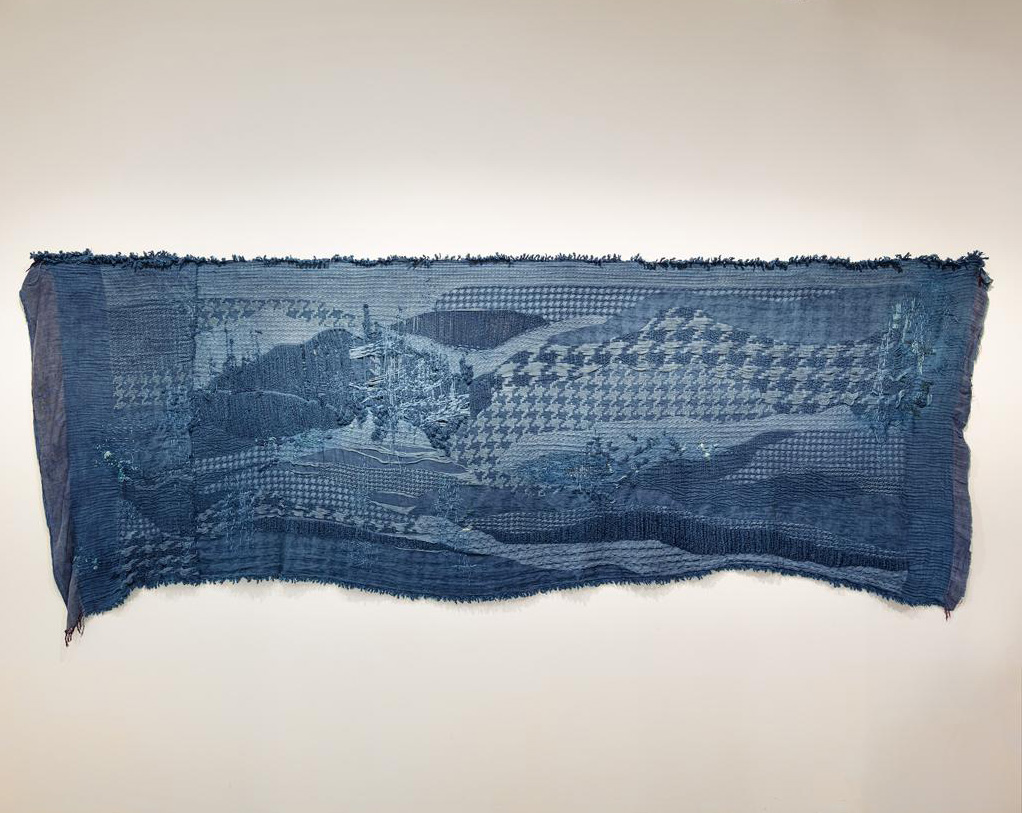

During my last couple of weeks, I worked on the Shepperd’s Touch artwork, a collaboration with the Textiel Museum in Tilburg. The work was inspired by a 2,800-year-old fabric remnant recently found in an Iron Age grave in Uden-Slabroekse Heide (Noord-Brabant). Following its analysis, scientists were able to identify a hounds tooth pattern in the fabric, once dyed with indigo and madder. Jongstra created an intricate woven piece which we dyed using an indigo fructose recipe from archival documentation. A feel of ageing and repair was crafted in by repeatedly distressing and mending the fabric, using the greenwoad and indigo dyed yarns from my previous experimentation. The embroidered piece is part of the “To Dye For” exhibition, celebrating the discovery and wider research undertaken, currently showing at the Textiel Museum.

Besides the creative and technical tasks carried out in the studio, I found the final stages of finishing and cataloguing the artworks particularly instructive. Equipped with an arsenal of needles, threads, tape, screws, and tools to tackle any eventuality, I joined the team on trips to Amsterdam and La Hague to install the completed artwork in its rightful place.

With my creative practice at a pivotal stage of development, I am hugely grateful to QEST for their support, and Claudy and her team for so generously sharing their knowledge, beliefs, and vision.

I have already implemented some practical changes to my practice—such as investing in a spin dryer(!)—and thinking through the steps required to make my work practices more sustainable and ethical. Whilst I won’t be dyeing my own materials quite yet, I’m able to reach out to specialist dyers with the right questions.

So, as I drove away from the village of Spannum for the last time, my thoughts dwelt on the invaluable learning I had gained, and more specifically, the clear sense of affirmation about my work, and excitement for what’s to come next.

As for living away from home for three months? Well surprisingly it was much easier than I had anticipated — a simultaneously grounding and uplifting experience!