Catching up with Book & Paper Conservator Edward Cheese

22nd August 2020

Why did you apply to QEST and what did your scholarship fund?

My 2005 scholarship paid for the tuition fees of the second, postgraduate diploma year on the Conservation of Books and Library Materials course at West Dean. Having used all my savings to fund my first year of study, I was worried about how to afford the second year of training which was crucial to being able to find employment as a conservator. Staff in the College suggested I get in touch with QEST, and I was extremely fortunate to be offered an interview and, following that, a scholarship.

Tell us about your scholarship experience?

My scholarship-funded year was an intense, all-absorbing experience, and I loved every minute of it! The scholarship gave me a personal boost in confidence and I was determined to immerse myself in the subject of book conservation as fully as possible to live up to the confidence QEST had shown in me. The second year of training not only enabled me to consolidate and hone my skills but also to experiment with binding structures for manuscripts and early printed books.

How did this impact your career?

Had I not received a QEST scholarship, I do not see how I would have been able to continue my studies at West Dean, much less find work as a book conservator at the end of my training. But, quite apart from the financial support, QEST’s rigorous interview process and insistence on the highest quality in craft work stays with me, and that is something I find deeply inspiring – aim for the best you possibly can, no matter what you are doing!

Can you tell us more about your subsequent career?

At the end of the course, I was invited to go and work with Melvin Jefferson and Elizabeth Bradshaw at the Cambridge Colleges’ Conservation Consortium, helping to prepare the manuscripts in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College for digitisation. I deeply appreciate that opportunity to work alongside highly skilled and experienced colleagues still! When the digitisation project came to an end, I became a full-time member of staff at the Consortium, and took over running it on Melvin’s retirement in 2011. In 2015 I moved a few hundred meters along the road to take up the post of Conservator of Manuscripts and Printed Books (Assistant Keeper) at the Fitzwilliam Museum, where I work on the great manuscript, printed book and archival collections, both at the Museum and Trinity College.

Any highlights?

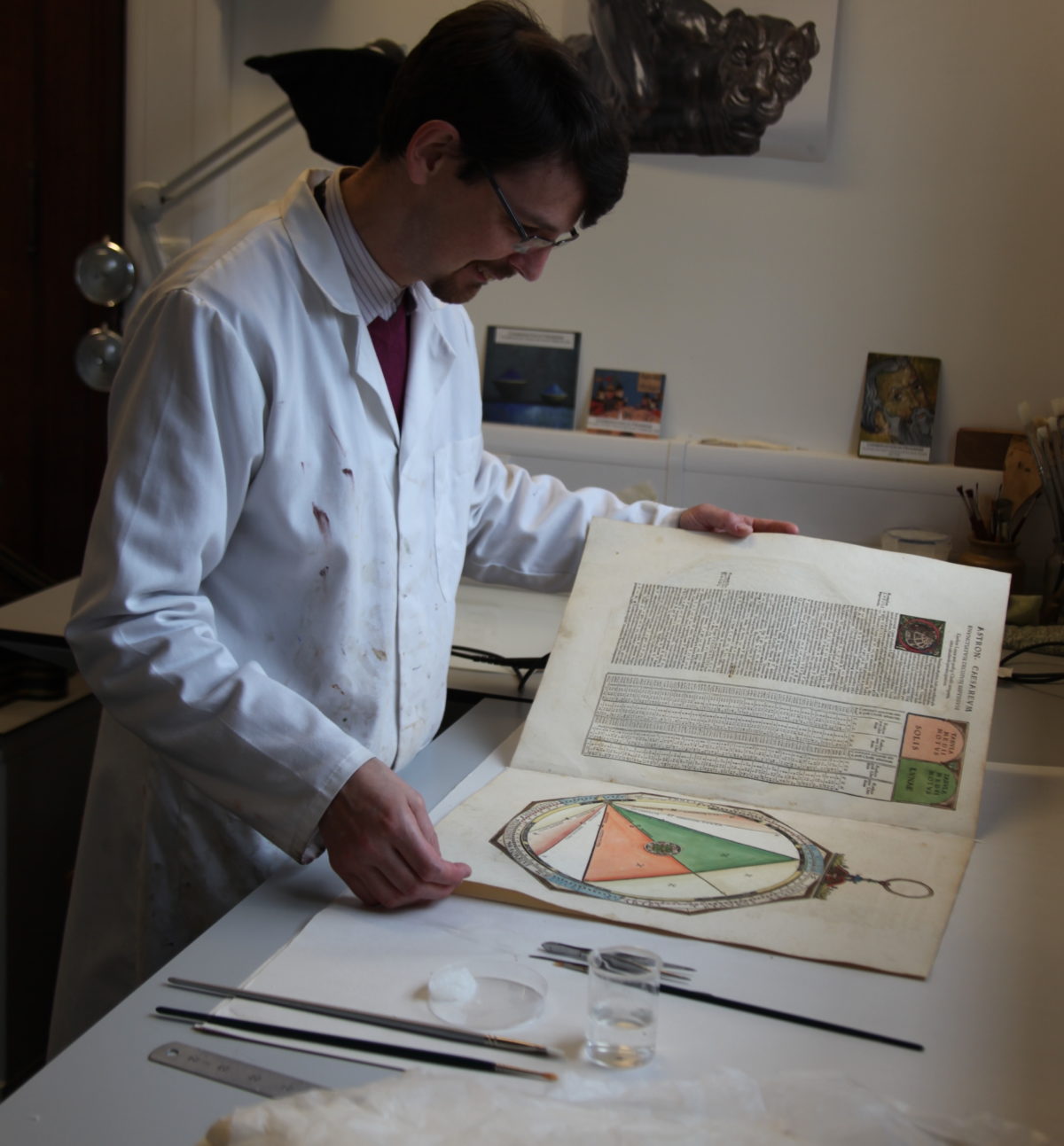

It’s always difficult to chose favourites, but I have been lucky enough to have been able to undertake several rebinding projects for important and very old books which were being damaged by inappropriate later bindings. These have included MS 251, a beautiful early fifteenth-century French manuscript, at the Fitzwilliam; the earliest book in the Wren Library at Trinity – the eighth-century Pauline Epistles; and, most recently, one of the treasures of the printed book collection at the Museum, Apianus’s Astronomicum Caesarium of 1540. In all these cases, it has been fascinating to work closely with the curators and be able to share experience with the other people, in person and online.

Can you describe some of the techniques that you most commonly use?

I specialise in the conservation of bindings on manuscripts and rare printed books, which involves combining thorough understanding of the materials and structures of the binding in question with repair methods and materials which disturb the historical evidence as little as possible, whilst also allowing the book to function properly again. In some cases, it is necessary to make new bindings for medieval manuscripts. I particularly enjoy this work, which is inspired by the structures and materials used by medieval craftsman and allows the manuscript to flow open beautifully.

What are you working on at the moment? Everyone’s world has been transformed by COVID-19, and the museum sector is no different. It was very sad to be at home and away from the bench for so many months, but it has been a good time to reflect on observations and ideas which practical work brings. We have also had chance to clean the whole Museum thoroughly, which has been exhausting but satisfying. I am very much looking forward to getting back to the bench, though, and to resuming repairs on the leaves of a tiny pocket Bible, which has very damaged, tissue-thin parchment leaves. It’s one of the most testing projects I have ever worked on!

What are your plans for the future? Practical work and craftsmanship are central to everything I do and I am keen to maintain that: you have to keep practising daily to maintain and develop your skills. Recently, however, I have also been involved in wider conservation initiatives, and have very much enjoyed contributing to the bigger picture of conservation principles across the profession and to developing educational opportunities to pass on practical skills.