Spotlight on Stone by Helen Chislett

7th February 2020

Last summer, I visited the Callanish Standing Stones on the Isle of Lewis. Standing in near horizontal rain, I was struck by the dignity of these ancient rocks, about four metres high on average, which give uninterrupted, 360-degree views to the distant horizon. The Callanish stone circle is said to date from 5000 years ago, older than the Pyramids, but what really struck me was that they are made of Lewisian Gneiss, a metamorphic rock thought to be about three billion years old – one of the most ancient of our planet. At this latitude, both the sun and the moon demonstrate wide variance over their cycles, with the moon in particular ranging dramatically over an 18.5 year cycle. In 2025, people will gather at the critical time to observe it rise out of the body of Cailleach na Mòintich, skim low over the horizon, set behind the hill of Cnoc an Tursa, and reappear at the foot of the monolith at the centre of the circle. This is as an ancient manifestation of the idea of “birth, life, death, and rebirth”, which also inspired the great, stone cathedrals of Britain many millennia later.

Stone is intrinsically linked to human development. The Stone Age lasted over three million years and is contemporaneous with the evolution of man, until the advent of metal tools around 2000 BCE. However, our love of stone has endured since earliest times, in particular as a material for imbuing buildings with grandeur and a sense of permanence. A walk around London takes on new meaning when focused on the stones used to create this iconic cityscape: the Portland stone of St Paul’s Cathedral; the limestone facade of Buckingham Palace; the grey granite of the British Museum and the Bank of England; the pale yellow limestone of the Houses of Parliament; and the grey Foggintor granite of Nelson’s Column. All of these stones were sourced from the British Isles – respectively Dorset, Bath, Cornwall, Lincolnshire and Devon. However, it is the Albert Memorial that represents the pinnacle of the decorative use of indigenous British stone: the architect George Gilbert Scott selected twelve varieties in all, including marble, crystal, jasper, agate and onyx.

We may be living in the 21st century, but stone is as relevant to our interiors today as it was in Roman times, used extensively in bathrooms, kitchens and as flooring. Designers describe the excitement of seeing an expert cut into a block of stone, because the result is always unpredictable – will perfectly book-matched, symmetrical patterns emerge or will the effect be more akin to Abstract Expressionism? In the quest for the perfect effect, our home-grown stones are often ignored by super-prime architects and interior designers, who prefer the glamour of visits to the Carrara marble quarries in Italy – admittedly an astonishing sight – but it is estimated we still have over 2000 active stone quarries in the UK.

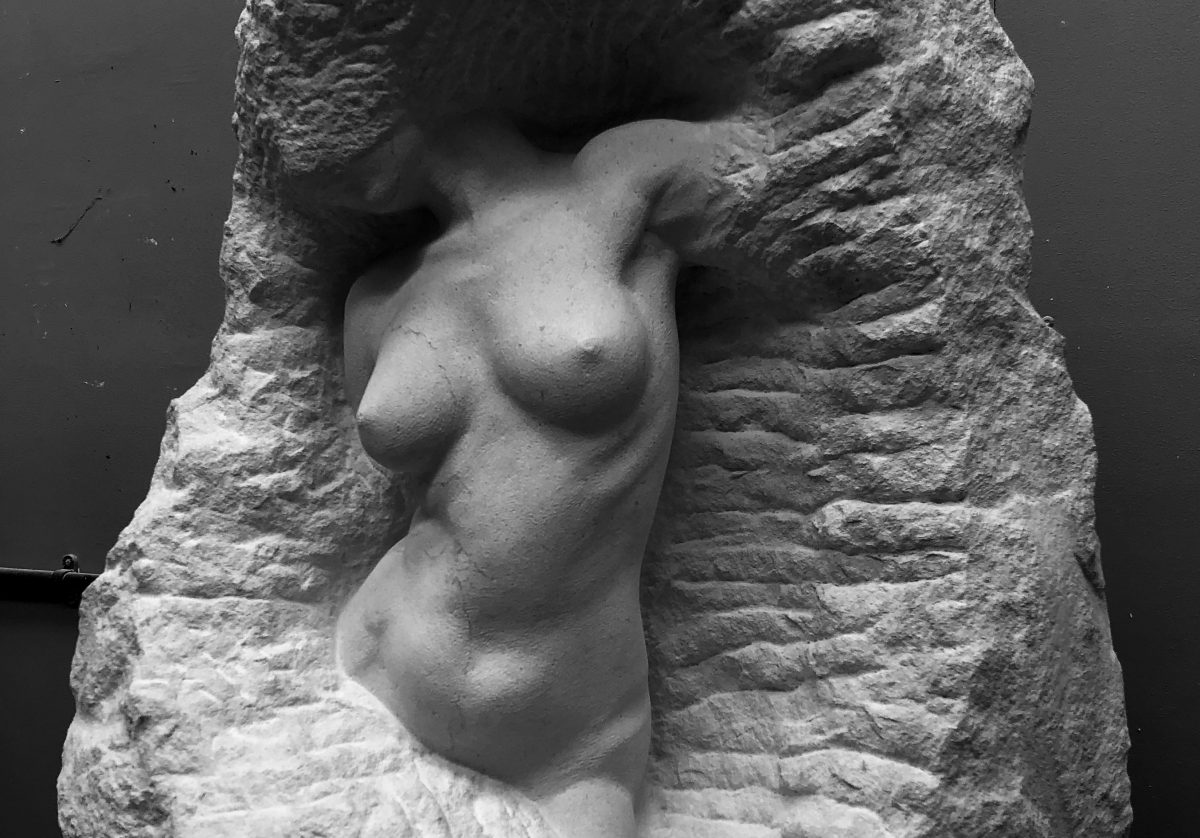

Where Italy does undoubtedly lead is in the working of stone. The Carrara region is not just the centre for marble of that area, but is the global trading point for stone imported from all over the world – including the UK and Ireland – because the specialist skills for the cutting, carving, honing, polishing and book-matching of stone are second to none. It was for this reason that John Sutcliffe chose to use his QEST funding to learn marble working at a workshop in Carrara. Having developed a successful career in sculpting and stone masonry, during which he had worked on projects at St Pancras, Gloucester Cathedral and York Minster, he was keen to learn more. “For me, it is all about taking my skills to the highest level possible.”

The pull of stone as a material is happily still inspiring new generations of artistic talent. QEST Scholar, Samuel Flintham, was inspired to study architectural stonemasonry, carving and conservation at the City of Bath University. He subsequently took the Architectural Stone Carving diploma at the City & Guilds London Art School, with the QEST scholarship enabling him to complete his training there, “While on the course I was lucky enough to win two paid commissions. The first was to design and carve a grotesque for Saint Georges Chapel, Windsor Castle, the second a sundial for Kennington Gardens. One of my projects, a copy of the giant Klytius from the Pergamon temple, won the Masons Company Carving Prize.” Today he has his own studio for working stone and also passes on his passion for the subject to his students at Bath College.

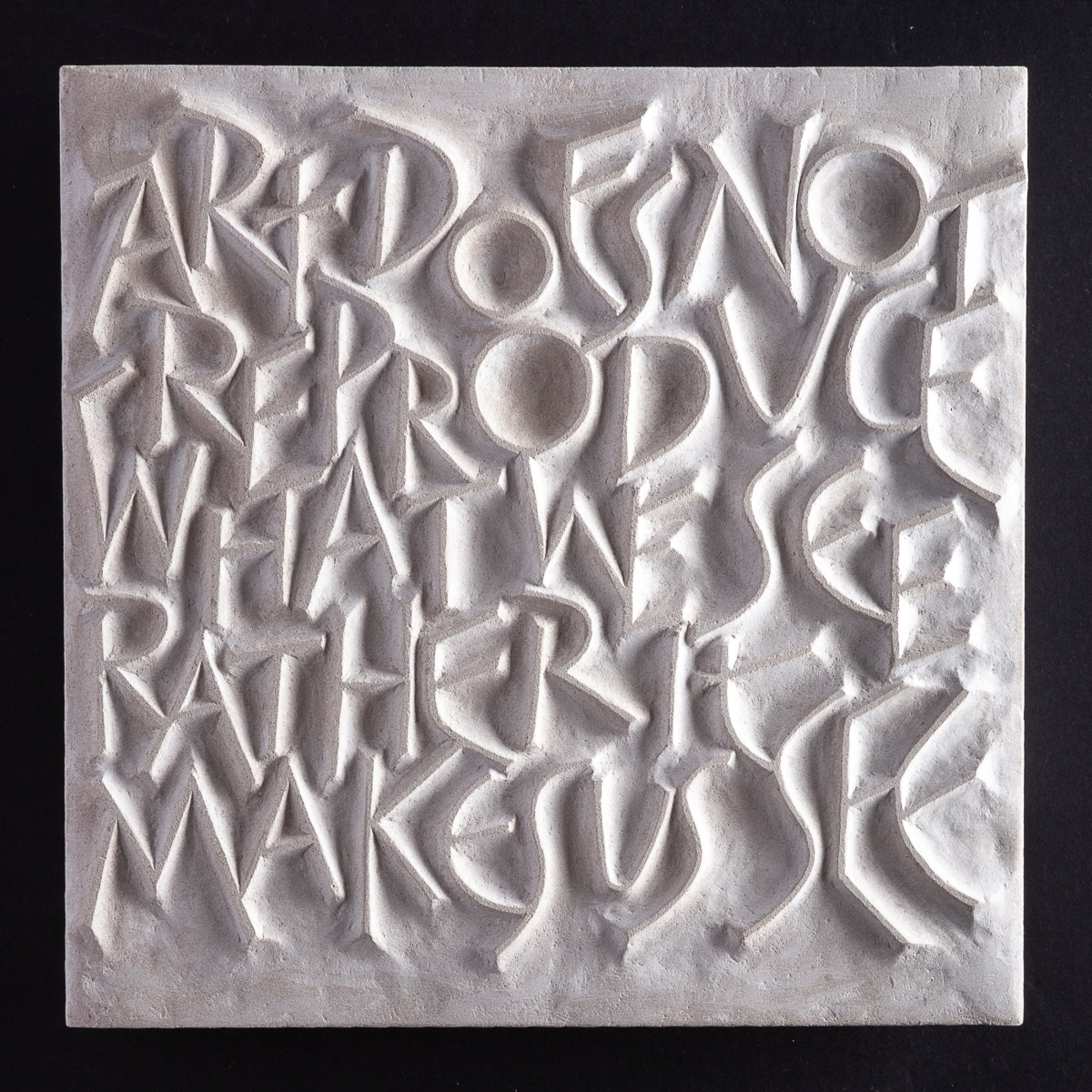

For me, the allure of stone is its longevity, versatility and tactility. Lettercarving on stone brings out all those qualities perfectly. While most usually associated with ancient graveyards, lettercarving has been chosen by many artists to create a sort of visual poetry. QEST Scholar, Lisi Ashbridge, is a self-taught lettercarver, whose funding from QEST enabled her to undertake one-to-one tuition with master lettercarver, Caroline Webb. Today she creates hand-crafted art pieces, including many bespoke commissions for garden settings. “Ideas can come from the changing seasons and from the sheer pleasure afforded by plants and the paraphernalia of gardening,” she says.

Perhaps lettercarving touches something deep within us because it harks back to ancient stones carved with runes and thought to have mystical properties. From the Isle of Lewis, I travelled 135 miles north-east to the Orkneys to visit Skara Brae, the stone-built Neolithic settlement on the west coast of Mainland, where you can still marvel at stone rooms with stone dressers, stone seats and stone beds, built over 5000 years ago. Carved stone balls were found here, with spiral ornamentation thought to be runic writing, but never successfully translated. Sometimes stone keeps its mysteries tight.

Stone symbolises forces that are both ancient and powerful, as with the Lewisian Gneiss of Callanish. But how heartening to know that, as a material, it continues to inspire and fascinate artists, designers and craftspeople today – including many QEST scholars – providing an unbreakable link from our past to our present; and from our present to our future.

Helen Chislett is a writer and founder of London Connoisseur: www.londonconnoisseur.co.uk

This article first appeared in the Spring 2020 edition of the QEST Magazine.